25 Feb Climbing the World’s Coldest Mountain

Introduction

The gravitational pull due to the Earth’s centrifugal motion is at its greatest on the equator. This means that the atmospheric pressure will be at its greatest and weather conditions at its mildest near equatorial postcodes compared to that of similar heights near the arctic regions. Kilimanjaro being near the equator and Denali near the Arctic are two mountains of similar height, but their distinct qualities could not be more contrasted. Please enjoy Ian Robinson’s account of climbing “the world’s coldest mountain”.

Climbing the Worlds Coldest Mountain

“A few grains of sand make a pebble, a few pebbles make a rock, a few rocks make a stone, a few stones make a boulder. So, go through your bloody gear and cut it down again” was the order from our expedition leader Thai Verzone.

“There are no Sherpas on the mountain to help you. It is just you, the ice, the mountain and the arctic” whilst showing a photo of a climber frozen solid dangling from his rope on an ice cliff just above medicine camp… “so keep your wits”.

Denali rising above reflection lake: photo Ian Robinson

On the floor of the airport hangar in Talkeetna, I drained my toothpaste, cut my toothbrush in half, pulled the cardboard out of the toilet paper and trimmed the straps on my back pack. A few more pebbles were now pushed aside.

Denali (or Mount McKinley) is North America’s highest mountain sitting majestically just shy of the Arctic Circle in Alaska. Its 20,320 foot summit rises about 18,000 feet from its base (compared to Everest’s 12,000 feet) making it the tallest (as opposed to the highest) mountain above sea level and is logistically buried deep within 6 million acres of remote national park flanked by the Alaskan Range.

Ian Robinson on Kahiltna Glacier hauling his 52kg load to the base of the mountain.

It was May 2001 and my preparation was hampered by a nation-wide quarantine in Ireland for a foot and mouth outbreak (yes I was living in Ireland at the time). This limited my training to hauling a sled full of rocks up a 30-foot gradient in a muddy field just 3 km south of Kilkenny. But in reality, nothing really prepares you for Denali.

Climbing Denali is a very physical endeavour. Each of us had to carry 52kg of supplies that was hauled up the Kahiltna Glacier via an integrated roping system of sleds and packs. Once at the base of the mountain, the sled was ditched for double carries, progressively hauling gear to higher camps which also assisted with altitude acclimation.

Each camp was dug into the ice and snow for protection against severe arctic storms

We were hitched four to a rope to save each other from a crevasse or a cliff fall for the entire climb. The front climber probed for crevasses, and on steep pitches would run the rope through carabiners attached to an ice picket known as an anchor hammered into the snow. We depended on each other everything, cooking, camp preparation, rope work, and rolling it up to its effective state of what it actually was, our lives.

Team member probing for crevasses whilst route finding up the glacier

Quite a few of our team dropped out early due to shear weight of the effort. You knew it was time for them when they fell in the snow they could not get back up without our support. So they gracefully retreated back to base camp.

Mid climb we picked up a hitch hiker whose team was retreating after a failed summit attempt. He introduced himself in his American drawl as Monty from the Air Force “Hi, I kill pilots. Our motto is shoot ‘em down first and sort ‘em out later…. He wanted another shot at the summit, and we voted him to fill a slot on our rope. Although his motto did not seem to fit the mountaineering creed.

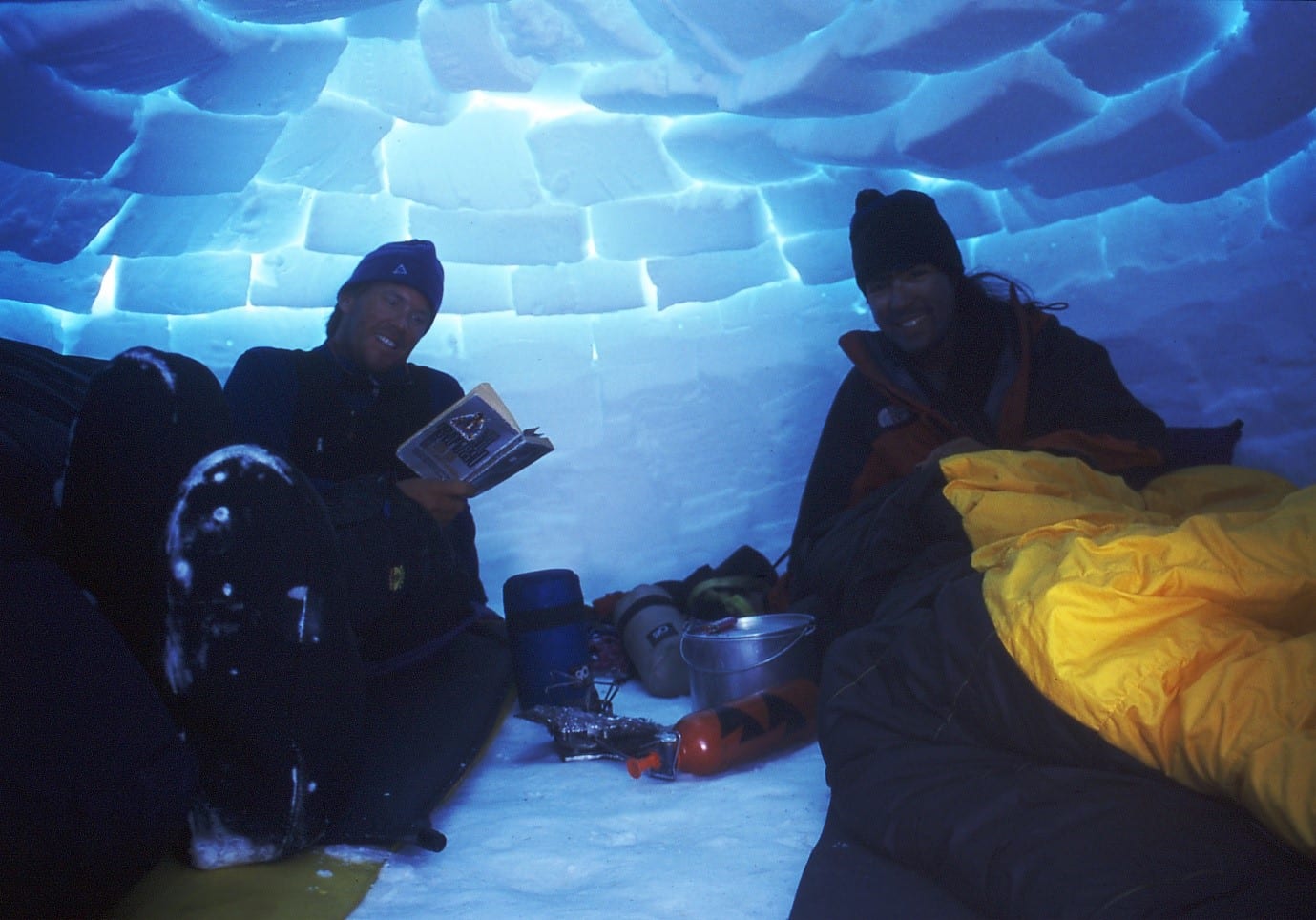

My anti-aircraft gunner and tent mate, Monty. During one of our evening drying sessions

On average there was 8 -12 hours of climbing per day, then add another 5 hours of camp and meal preparation. Both feats were no easy task. Usually buffeted by winds, exhausted from the climb and wearing thick mitts made for some challenges, but the process was not optional. It was necessary. Our tents had to be dug in. Either through the construction of an ice wall or an igloo. Melting snow on our single burner cookers was a constant chore to try and keep the fluids up. Temperatures midway up the mountain were now hitting -30 degrees so the sheer mathematics of a small exposed naked flame combatting the natural environment was almost comical.

A tent dug in at 14,500 feet. There was a whole warren of trenches and wombat holes. Life only emerged at the surface when it was time to move

The world that wrapped around us was a vertical world of rock and ice. Long periods of silence would suddenly explode with avalanches breaking away from the mountain side and filling the glaciated valley’s void with clouds of ice.

There would be four phases to these most incredulous events when witnessed firsthand. First, the avalanche would commence its exponentially growth trajectory down the mountain in complete silence, abstract to the sheer velocity and destruction that it entails.

Then the roar of its kinetic power hits like thundering low flying jets. The sound akin to apocalypse.

The third is the invisible wind storm that slams into you as the avalanche pushes the air mass in front like a stratospheric bulldozer.

The fourth is the holy shit moment when you quickly calculate if your position is safe from its path, noting that the time lapse to move from the first three memorising phases to phase four is about 0.5 seconds.

My igloo at Medicine Camp, 14,500 feet whas was a nice stable – 10 degrees being much warmer than a tent

Climbing big mountains is an unpredictable venture. Good decision making and good management assists in reducing controllable risk. It is the uncontrollable nature of mother nature whilst operating in a fragile environment ultimately determines fate and outcome.

Ian Robinson standing on the summit of Denali with the Alaskan Range below. Temperature -40 degrees

Not all went to plan. Our retreat from the summit was met with the news of an encroaching arctic storm. We did not have the provisions to bunker down at high camp, so we made the decision of an immediate and enduring push down the medicine camp.

Storm coming in over the Devils Thumb. Notice the two small climbers on the ridge line just above the Thumb

I don’t think you are ever prepared for the full force a nature when confronted at a time of vulnerability. Sleep deprivation and nutritional starvation compounded the consequences of our choice to retreat in its path.

The mountainous terrain between camps entail exposed ridgelines, ice cliffs and rocky bluffs that provide no retreat or reprieve. At this point two of our climbers now succumbed to the elements. Greg incurred incapacitating frost bite on his hands and feet which completely disabled him from functioning the ropes through the anchor points. Fred just outright collapsed.

The wind meanwhile vortexed over the knife edged ridge hitting us with accelerated compression. Compensating for wind chill had us downclimbing in – 55 degrees. Our retreat was now a rescue. For greater mobility we had to disengage our ropes from the anchors that protected us from falling but exposed us to the ultimate consequence if anyone did.

Our team was operating on the margin when, through his failing efforts, Fred remained hung upside down and unconscious on the ice cliff with his dead weight pulling heavy on the anchor point. This abseil was our only access off the ice cliff, and we were caught above Fred locked on the rope. It was also exactly where the photo was taken of a frozen climber showed to us in the airport hangar.

I personally focused on getting Greg down the technical pitches challenged by his frost bite whilst the others lowered Fred.

Japanese Express, a very steep part of the climb where, for many decades, Japanese climbers found their grief from falling off this traverse.

We all did get back down with a full head count. Fred broke down in tears with gratitude that comes with salvation and Greg ended up sponsoring my next climb in the Himalaya as a quite thank you of good will.

It is obvious that mother nature’s boundaries operate well beyond our personal limitations. Playing on its fringes develops an enriched respect of our mortality and quietly humbles the most ambitious.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.